Narrowing the language gap

How machine intelligence is transforming creative tools

Illustration by Joslyn Reid

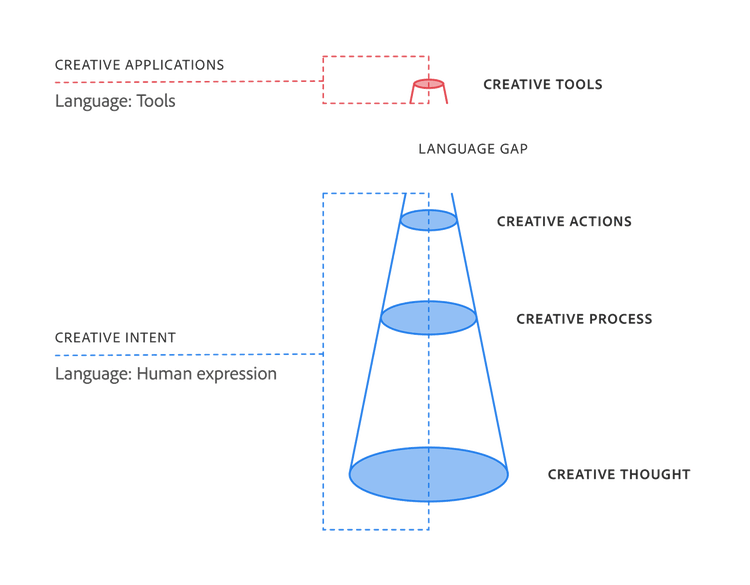

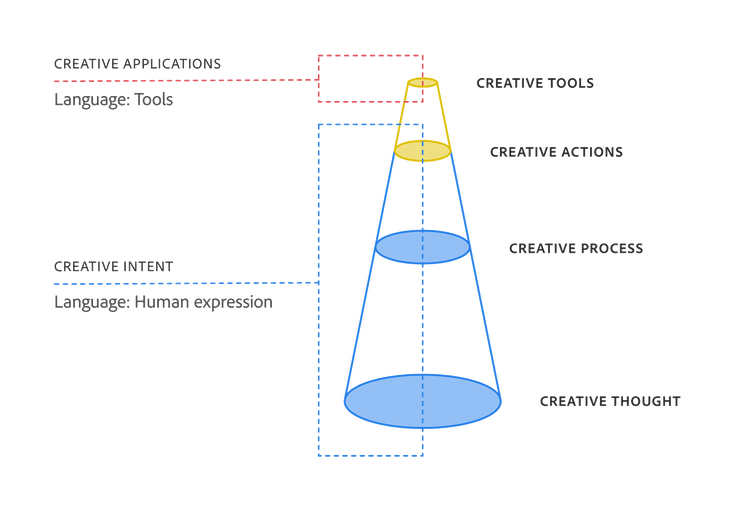

There’s a language gap in today’s creative landscape. One that separates our creative applications from our creative intent. The gap is the reason we are required to “onboard,” the reason we find ourselves disoriented when a button moves after a software update, and the reason we watch online videos to learn features our tools have in fact offered for years. We accept the gap, because the historic nature of computers—binary execution of preprogrammed functions—has caused it to always be there. This gap demands that users speak like computers so they might effectively use computers.

Exposing our creative limitations

Today’s creative applications could be described as a collection of digital tools: a digital paintbrush, a digital typesetter, a digital brightness control. Together, they deliver an experience that asks users to translate their creative intent into a sequence of tools. For example, to “highlight the colors of the sky” in an application such as Adobe Photoshop might translate into the following tool sequence: Magnetic Lasso Tool > Hue/Saturation Tool > Brightness/Contrast Tool.

There are multiple tool sequences that could achieve any one of a user’s creative intents. Common sequences can even turn into their own vocabularies and language shortcuts around certain creative tasks. Single tools can also achieve an array of outputs depending on how they’re used and manipulated.

The language gap reveals limitations that users persist through as they exercise their intent within creative applications. Here are three:

First, their ability to enact creative intent is limited to the language of tools. Users cannot successfully use an application unless they interact with it using that same language.

Second, their ability to enact creative intent is limited to their knowledge of the tools available to them, including their ability and availability to learn new tools. If a user’s intent extends beyond their knowledge, they must either consult documentation outside of the application, or alter their course toward the use of familiar tools.

Third, their ability to enact creative intent is limited to the capability of the tools available to them. If a user’s intent is greater than the function of their tools, they must either change their intent or look for new tools.

Inspiring creative sameness

Two decades ago, creative technologist John Maeda was interviewed by the New York Times. He talked about the language gap in relation to Adobe tools:

Maeda recognized a consequence of the gap: The language of tools can subvert the language of creative intent. Rather than continue translating intent across the gap, users can instead develop a habit of formulating their intent directly in the language of the tool. Maeda describes the outcomes of this phenomenon as “homogeneous styles,” a sameness that emerges when creativity starts at the opening of an application and is then led only by the tools that the user knows. Maeda’s sentiments are echoed in this familiar quote:

Our language of intent

If the language of tools is by nature binary and mechanical, the language of intent is contextual and human. Intent from the perspective of a creative application is “select the brush tool and place four brushstrokes on the artboard,” while that same intent from a user might be “turn a chair into a barstool.” Intent can also be vague and multi-layered: vague, because another user could achieve the same outcome with “make the seat taller,” and multi-layered, because the task might contribute to a greater intent of “redesigning a restaurant interior.”

When directing his junior designers, graphic design luminary Massimo Vignelli would famously describe a visual layout as needing to “bang” or have “reverence." His intent could simultaneously be classed as human, contextual, vague, and multi-layered all at the same time; his designers could only learn the true meaning of the direction through experience. It highlights the multi-dimensional complexity of creative intent, and raises the question as to whether a creative tool can accept and facilitate “bang” in the way Vignelli meant? Will technology allow for a narrowing of the language gap?

Narrowing the gap with machine intelligence

At the beginning of this essay, computing was described as a historically “binary execution of pre-programmed functions." In this style of computing functions are rules-based, and rules are pre-programmed into software before their release. The resulting functions are defined, engineered, and inflexible to adaptation.

Machine learning offers an alternative style of computing that takes a different approach. Here, intelligent computing is still rules-based, but the rules are not preprogrammed. Instead, machine intelligence infers what the rules should be after recognizing patterns and relationships in a dataset. This method allows intelligent functionality to be adaptive to the individual user and follows rules that are calculated to best meet each individual request. This logic allows a pair of users to input the same search term and receive different results, or a single user to input the same search term at different points in time and be given different results. In both instances, a greater number of inputs beyond the single-given search term are utilized to calculate the most relevant result.

Through contextual learning and dynamically refined outputs, machine intelligence offers to learn the language of the user, and in doing so observe the subject and context of a user’s content. In recognizing the human language of intent, users are empowered to engage their creative applications without first needing to learn the language of tools, and creative applications are empowered to “highlight the colors of the sky” or “turn a chair into a bar stool."

Below are visualizations of “turn a chair into a bar stool” and “highlight the colors of the sky.” The first images (top) show the steps taken when translating creative intent into the language of tools. The second (bottom) suggests what’s possible as the language gap is narrowed.

Narrowing already

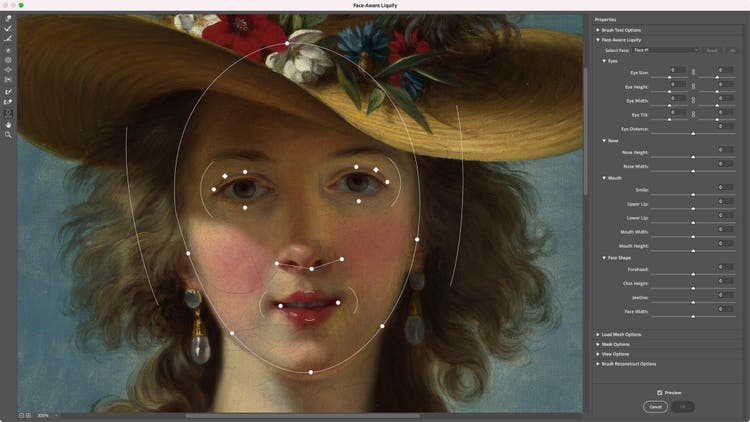

We’re already starting to see the language gap narrowing in today’s creative applications. Below, Photoshop’s “Face-Aware Liquify” feature allows for the semantic editing of human faces.

Thinking beyond "smart" tools

Advances in machine intelligence are narrowing the language gap, that creates a divide between creative applications and creative intent, allowing us to reimagine experiences of the next creative wave. These applications won’t just offer a collection of enhanced “smart” tools, they’ll offer a deeper dialogue between a user and their creative intent; they’ll be active facilitators in the creative process and of our creative navigation; they’ll bring new creative possibilities for application users and application makers alike.

Further thinking

- Think about the time you spend in digital applications today: Are there any current tasks or workflows that feel particularly shaped by the language of the tool? How would you expect those experiences to change in response to narrowing language gaps?

- Are there examples of narrowing language gaps that you’ve already encountered in digital experiences you use today (maybe some that aren’t creative tools)?

- Based on your current knowledge of machine intelligence (just the information in this essay is enough), imagine or sketch a new feature that’s built around a creative intent and the language of content.

- Are there creative intents you can think of that are literally impossible to achieve in today’s creative applications because of the language of tools? (This question is deliberately obtuse.)

This article originally appeared on Medium with the title "We’re Shaped by Our Creative Tools."