Writing is designing

A book about words and the user experience

Illustration by Eirian Chapman

Andy Welfle, UX content strategy manager at Adobe, and his friend and workshop partner Michael J Metts' book, “Writing Is Designing,” tackles this very topic. Its goal is to empower the “words-person” at any product company—copywriter, content strategist, support tech, project manager, designer—to think of writing as a design practice and to get the tools they need to write interface language clearly, consistently, and conversationally.

We sat down with Andy to find out more about UX writing, what he calls "designing with words," and asked him how writing and design are related, the difference between voice and tone and how they create and deliver effective user experiences.

Why is UX writing becoming so popular? How are writing and design related?

There has always been someone who writes the words in software interfaces. But traditionally, it’s been more of an afterthought, or done by people in separate silos and in different parts of the practice. Increasingly, though, as UX as a practice has become more important to the functionality and system of software, we can see how a UX methodology really aids the writing. (When I say “a UX methodology,” I’m referring to a user-centered design approach to building a product—something that focuses on solving real user problems and aims to be as simple and clear as possible.)

Just as UX designers incorporate brand elements into their designs in a usable way, UX writers think about brand voice and how it manifests itself in the product. As designers think about components like buttons, forms, and dialog boxes, UX writers think about terminology and action words. The approach is the same, based on iterative, collaborative, and tested research. UX designers and UX writers share the exact same goals they just use different content types to do it.

What will readers learn from Writing Is Designing?

Hopefully people will learn some of the core tenets of UX writing—why it’s important to make sure your message is clear and concise, and how to do that.

We dig into error messages and stress cases and give tips on what purpose they serve (hint: the best error message is one that doesn’t have to exist at all). We take concepts like “voice” and “tone” and break down the differences between them to give readers a system to use them strategically and consistently.

How important are voice and tone to effective user experiences?

They’re important. Voice is a very effective way for a product to build a relationship with the user, and to bring forth the company’s brand. Sometimes they're the same: Slack’s corporate brand voice is identical to their product voice. They make the same word choices, they present the same values, and talk to the users in the same way.

But sometimes, an app’s voice is different than the corporate brand’s voice. And that’s okay, too. Look at how we do things at Adobe—our brand speaks to our customers in a way that shows our intersection of art and science—we’re passionate and captivating and really excited to help customers create. Just browse around Adobe.com and see how that manifests. But once customers become users, and download our apps and start using them, we take on a more distilled version of that voice. Our interfaces, particularly for our desktop software, can be complicated and technical, so to get people using our apps, our priorities switch to being as clear as we can be. We have a different set of goals and principles.

So, while voice should stay consistent throughout the experience, tone is what lets you switch contexts and better respond to a user based on what’s happening. Just as I, Andy, have a single voice, my tone changes depending on whether I’m talking to my mom, my coworker, my boss, or my college roommate. It can also change depending on whether I’m happy, or sad, or angry, and it can change yet again depending on whether the person I’m talking to is happy, or sad, or angry. The same should hold true with your UX writing.

So how do you set the tone for a digital product?

When I worked at Facebook, I learned how important it was to develop a framework of tone, so that this nuanced way of writing could scale across a big writing team. Check out this fantastic article by Jasmine Probst (who I interviewed for the Tone chapter of our book!) and Susan Grey Blue about how they develop a tone framework at Facebook.

One of the most valuable parts of this process is the questions you ask about any given scenario someone might encounter in your product. According to the Facebook content strategy team, you should ask yourself these questions to help craft the framework of tones:

- What is someone likely to be doing when this message appears?

- What is their mindset likely to be?

- What is the intention we’re showing up with in the UI? What do we want to offer people in the UX?

- How receptive is the person likely to be to that intention?

- How might we express that intention in a way that feels authentic? (Knowing we might be interrupting or dealing with someone who’s got any number of life things going on.)

Can you give us an example of a brand, other than Adobe, that gets UX writing right?

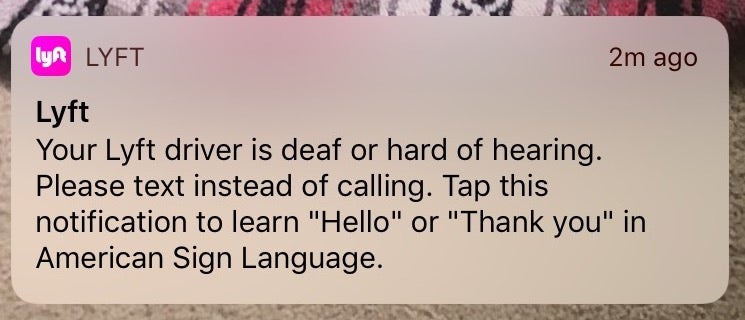

I really appreciate the UX writing efforts of transportation network Lyft. Although they had a few writing hiccups in their early days, I think they do an amazing job of not only capturing Lyft’s brand voice, but also explaining complicated concepts simply and in a contextually relevant way. They’ve been industry leaders in inclusive writing practices as well—among the first to allow users to choose their pronouns and supply options for disabled drivers and riders.

How do you ensure your design team develops a strong writing practice?

That’s a good question, and a hard one, because I think it varies widely from team to team. Here at Adobe, I was the first UX writer on a 300+ person design team, and for a year or so, before we were able to hire more people, I took a two-pronged approach:

- First, I found a product design team to embed with so I could really understand the Adobe way of building products. It’s important to find a team that’s flexible and game to experiment with how a writer can make an impact.

- Second, I became an evangelist. I invited myself to every team weekly that I could find to spread the gospel of UX writing—not only to ask for resources, but also to get designers excited about words and to learn how they can be used as design tools.

What inspired you to collaborate with Michael to write this book?

Michael and I met back in 2014, when I attended a content strategy workshop he was teaching at MidwestUX in Indianapolis, and we hit it off right away. I was on the verge of leaving a small web development agency in Fort Wayne, Indiana, to interview at Facebook for a content strategy job, and since he was one of the first product UX people I'd met, I had many questions for him.

Later, we met again at the 2015 edition of Confab, probably the largest content strategy conference in the world. We struck up a conversation at lunch about how there really weren’t any workshops or talks that spoke to what we were interested in—writing interface language, and how to collaborate with design teams as writers—and finally, he said, “Why don’t we make a workshop for that?”

We did, and pitched it to Confab, and they accepted! We’ve been doing that Confab workshop for the last four years, and have done it in other states and countries, too. Eventually, Kristina Halvorson (CEO of Brain Traffic, the company that organizes Confab) introduced us to Lou Rosenfeld, who owns Rosenfeld Media, a UX book publishing house. He was looking for a book about UX writing, and after an intensive pitching and outlining process, we had a book to write!

Michael and I collaborate well together. Although he’s in Chicago and I’m in San Francisco, our working styles complement each other. Our general interests and practices are different enough to provide well-rounded content, but similar enough to make sure we’re writing to the same goal.

Apart from buying your book, how can designers get started with improving their writing skills?

If you work on a design team at a large organization, there are bound to be other writers there, even if they’re outside of your organizational silo. I’d recommend connecting with them, and maybe even inviting them to your design critiques. Also, when you test your designs make sure to spend extra time on the language and the terms you use in your interface. It’s just as important, and sometimes even more important, as the visual layout and interaction flow.

The more you start thinking about writing as a design process, the clearer the power of words will become.